The ancient city of Nara, Japan has a long history over 1200 years.

There is a corner of the alley that runs off the main street of Naramachi, where old-fashioned, quaint old private houses are dotted about, where rows of row houses line the street.

This is a small street that has been reborn as a cafe and a general goods store.

One of these is Chiyomi Tanaka’s traditional Nara brush workshop and store.

Tanaka decided to become a brush artisan in 1983. At the time, she was a full-time housewife with young children.

She became the first woman in Japan to be certified by the Japanese government as a certified traditional artisan of brush making, and she is one of only seven such artisans in Nara.

She says, “When I was young, I worked as a designer for a printing company, but after I got married I became a full-time housewife. However, I felt uncomfortable being called ‘Mrs. Tanaka’, and I always felt a dilemma about wanting people to recognize my own existence.

The desire inside me to ‘try something myself!” grew bigger and bigger every day. However, I spent my days in agony, unable to find anything that really appealed to me.”

One day, Tanaka found that the government was running a program to train successors to traditional crafts. The program was a one-year course for training artisans, with no tuition fees.

She thought, “This is it!” and immediately signed up, and there were even times when she attended the class with her baby.

She had already mastered Japanese traditional flower arrangement and tea ceremony. However, she says that these lessons were not useful in her married life.

She had also learned how to sew kimono and Western clothes, but nothing caught her interest until she tried making brushes.

After completing the brush artisan training course, Tanaka joined a brush manufacturing company and spent her days immersed in brush making under her master.

“Back then, making brushes was considered a man’s job. Because you have to pluck the animal’s hair to get good quality materials. How horrible! I didn’t know that when I started, but by the time I realized it, it was too late. It was so fun and interesting that I didn’t care about that.”

At that time, it was normal for Japanese housewives to support their husbands by doing knitting, Japanese dressmaking and Western dressmaking.

There were even people who criticized her for working. However, once she started, Tanaka says with a smile, “I became addicted to the art of brush making.

After working for a Nara brush manufacturer for five years, She decided to set up her own shop and start selling brushes directly to customers.

She says, “People around me were very worried. There were some tough times, but thanks to the people around me, I managed to get through it. One time, when a long-established inkstick artisan was holding an exhibition, he said to me, ‘Let’s display your brushes together. I’ll even waive the commission. It was completely out of his kindness. I was still unknown at the time, so I was so happy I cried. It was tough starting from scratch, but it was also a lot of fun.”

Tanaka’s daughter, who lives nearby, helps out with her brush-making classes and exhibitions in her spare time as a housewife.

She has been watching her motherr’s work since she was a child. Tanaka says, “I secretly hope that one day my daughter will take off her nail polish. Brush artisans are not supposed to wear nail polish.” She laughs mischievously.

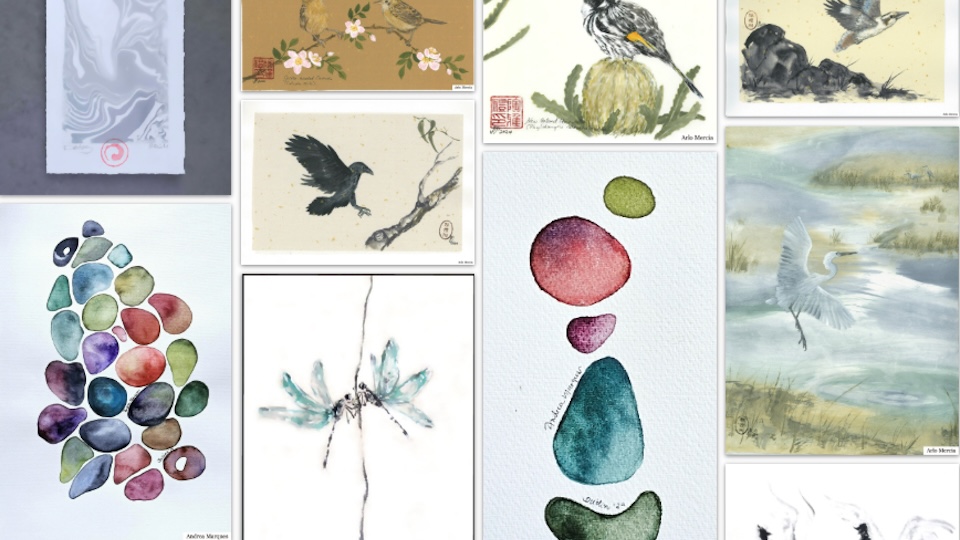

She says that many of the people who visit “Nara Brushes Tanaka” to look for brushes are calligraphers, painters and other talented, unique individuals.

“If you make a brush that doesn’t match the customer’s wishes, they won’t be happy. When you finally get to hold the brush you’ve made, after modifying the length and thickness until it matches the customer’s wishes, and they’re happy with it, that’s when you feel like you’ve done a good job.”